Article of the Month -

September 2006

|

Issues in the Governance of Marine Spaces

Dr. Michael SUTHERLAND and Dr. Sue NICHOLS, Canada

|

Michael Sutherland |

Sue Nichols |

This article in

.pdf-format

This article in

.pdf-format

1) This paper is the introduction chapter of FIG publication

“Administering Marine Spaces: International issues”. This publication is

result of FIG Commissions 4 & 7 Working Group 4.3. FIG publication 36,

Copenhagen 2006, ISBN 87-90907-55-8.

Abstract

Good governance is based on recognition of the interests of

all stakeholders and inclusion of their interests where possible. Interests

can be expressed in a variety of ways, for example: sovereignty,

jurisdiction, administration, ownership (title), lease, license, permit,

quota, customary rights, aboriginal rights, collective rights, community

rights, littoral rights, public rights, rights of use, and public good.

Coastal states are challenged with managing the multidimensional tapestry of

these interests (and perhaps others) in the coast and offshore. Over the

next few decades those responsible for marine policy and administration have

been challenged with trying to understand this tapestry and communicating it

to the various decision makers and stakeholders. However, addressing the

complexities associated with these interests solely from a boundary

delimitation perspective does not necessarily improve the governance of

marine spaces. This paper explores a number of legal, technical, and

stakeholder issues related to governing marine spaces.

1. INTRODUCTION

The governance of any geographical area, including marine

spaces, is actually the management of stakeholder relationships with regard

to spatial-temporal resource use in the pursuit of many sanctioned economic,

social, political, and environmental objectives. Good governance is based on

recognition of the interests of all stakeholders, and inclusion whenever

possible. Governance involves setting priorities that may establish

hierarchies of interests, but the basis is recognition of what is excluded,

as well as what is given priority in certain situations.

These interests can be expressed in a variety of ways, for

example: sovereignty, jurisdiction, administration, ownership (title),

lease, license, permit, quota, customary rights, aboriginal rights,

collective rights, community rights, littoral rights, public rights, rights

of use, and public good. One feature of being a coastal state is that there

is a multidimensional tapestry of these interests (and perhaps others) in

the coast and offshore. Marine administrators are challenged with trying to

understand and communicate this to the various decision makers and

stakeholders.

A marine cadastre, or other marine information management

system, serves to meet the information requirements for governance of marine

spaces by facilitating the management of thematic information and their

boundaries and limits. In past research we initially assumed that spatial

delimitation of interests would help clarify resource management and use

regime in marine spaces. What was learned from our research was that this

approach was very limited and probably impossible. The main reason is that

there are numerous marine boundaries, and four dimensions at least had to be

considered. Drawing lines on charts was often not feasible, legally valid

nor of value. The legal profession taught us that there were a myriad of

boundaries: at least one if not more for every resource and every resource

use. Starting from the boundary perspective was a nonstarter.

Effective governance of marine spaces requires that a number

of things need to be considered including:

-

the need for inclusion;

-

the need to change our concepts of a cadastre to deal with

multiple interests for the same space at the same time;

-

the difficulties in identifying, yet including, all the

stakeholders;

-

the importance of information, not necessarily precise

boundary delimitation;

-

the need to develop tools better than the traditional

cadastre to govern marine spaces effectively.

To address the listed considerations, this chapter will

explore the governance of marine spaces by focusing on a number of

stakeholder issues, legal issues, and technical issues. However what is

meant by governance will first be discussed.

2. GOVERNANCE

The governance of marine spaces is the management of

stakeholder activities in these spaces. To optimize this management and to

address stakeholder issues requires that effective governance frameworks be

in place. Collaborative, cooperative, and integrative governance are

improved frameworks for dealing with stakeholder issues. Traditional

governance models have been based on a management science approach where the

premise is that leadership of organizations (public, private or civic) is

strong, and have good understanding of their environment (future trends,

rules of the game, and the organization's goals) [Paquet, 1999]. As such,

the leaders provide direction for the groups they represent.

A hierarchical governance model is one such example. This

form of governance, usually practiced by the state or some other governing

authority, is usually enacted through policies, laws and regulations

[Hoogsteden, Robertson and Benwell, 1999; Paquet, 1999; Savoie 1999]. This

hierarchical model assumes a top-down approach is always best, whereas

subsidiarity (i.e., the principle based on the assumption that individuals

are better able to take care of themselves than any third party) might

alternatively provide a better solution in some circumstances. Subsidiarity

would support, for instance, the devolution of responsibilities to citizens

by provincial/state authority (or to states/provinces by federal authority)

as much as possible unless they were unable to manage [Rosell, 1999;

Chiarelli, Dammeyer and Munter, 1999].

The management science approach also assumes that

organizations are operating in "a world of deterministic, well-behaved

mechanical processes" [Paquet, 1999]. However, life is full of paradoxes,

contradictions, and surprises [Handy, 1996], so the management science

approach has been inadequate, continually faced with situations that are

ill-defined, uncertain, unstable, or unreliable. As a result of the failure

of the management science approach to governance to adequately handle all

the complexities of life, other models have been proffered. These models are

based on cooperation, coordination, collaboration, integration or other

principles of shared responsibilities. The similarities or overlaps in the

definitions of these models again underscore the absence of general

principles to help guide in the design of good governance structures

[Paquet, 1999]. Among these models are:

-

Distributed governance which is embedded in a set of

organizations and institutions built on market forces, the state, and

civil society, and which deprives the leadership of the exercise of

monopoly in the direction of the organization. [Paquet, 1999; Meltzer,

2000];

-

Co-governance (e.g. practiced on a state-civic level) that

comprises mutual organization by two or more involved groups [Charette and

Graham, 1999; Hoogsteden, Robertson and Benwell, 1999];

-

Triangle-wide governance that consists of the integration

of the three families of institutions (economy, society and polity) into a

sort of neural network [Paquet, 1999; Meltzer, 2000];

-

Transversal and meso-innovation systems of governance that

employ “consensus and inducement-oriented systems to achieve coordination

among network players” [Paquet, 1999];

-

Renaissance-style independency forms of governance that

utilize informal terms, and the devolution and decentralization of

decision-making to achieve its objectives [Paquet, 2000].

These models are by nature subversive to those

organizational structures based on traditional models of governance. They

challenge the view that an "omnipresent person or group has monopoly on

useful knowledge and can govern top down" [Paquet, 2000].

There are many definitions of governance. Some of these

include:

-

“The process whereby a society, polity, economy, or

organization (private, public or civic) steers itself as it pursues its

objectives” [Centre on Governance, 2000; Paquet, 1994; Paquet, 1997;

Rosell, 1999].

-

“The process of decision-making with a view to managing

change in order to promote people's wellbeing” [Kyriakou and Di Pietro,

2000].

-

“The set of processes and traditions which determine how a

society steers itself thereby according citizens a voice on issues of

public concern, and how decisions are made on these issues” [Meltzer,

2000].

-

“The guidance of national systems shared by ensembles of

organizations rooted in the three sectors (economy, polity, civil society

and community)” [deBlios and Paquet, 1998].

-

The means by which local, regional, national and

international communities organize themselves and subsequently respond to

issues of interest to members of those communities. It involves leadership

on the part of government and the use of policy and programs to control

and influence activities within communities [Manning, 1998].

A number of points essential to governance are alluded to in

the above definitions. Firstly, governance is all encompassing, touching

virtually every area of human existence. Secondly, governance can take many

forms, and takes place on many levels. This is supported by Masson and

Farlinger [2000]. Each form of governance makes use of facilitative

processes, mechanisms and systems to pursue goals. Thirdly, governance is

about the provision of direction towards the achievement of objectives. The

direction taken must take cognizance of the interests, rights,

responsibilities, and differences among all stakeholders.

3. STAKEHOLDER ISSUES

Practical problems in governance include:

-

how identify who the stakeholders are;

-

how to engage them effectively; and

-

how to manage their input, including keeping the dialogue

going over time.

This can be summarized as defining the governance process in

terms of liaising, listening, learning, and leading. Too often agencies

responsible for programs and projects focus only on the last step.

3.1 Stakeholder identification

One of the greatest limitations in most marine programs and

projects is having a narrow approach to stakeholder participation. This is

often driven by issues such as: time constraints, lack of knowledge, single

issue focus, or governmental silos. It is particularly true in coastal

region were there may be jurisdictional uncertainty, overlaps, and gaps.

However, the top down approach, while perhaps being the easiest to manage,

is also the least likely to have sustainable results. Spending time at the

local level in the initial stages of marine activities (e.g., through

workshops and town hall meetings) can help to identify the breadth of

stakeholders and their interests.

3.2 Effective Stakeholder Engagement

Effective consultation is not just “this is what we are

going to do for you.” Frequently, information meetings allow question

periods but do not include processes for taking and putting input to use. A

variety of means can be used to obtain input including web portals. The

information provided for consultation also has to have the right message and

medium for the variety of different audiences.

3.3 Managing Stakeholder Input

Once input is obtained, consensus building strategies are

required to establish priorities and identify appropriate solutions.

Frequently the priorities are different at the local, regional, and national

level. Whoever is leading also has to listen and learn if the differences

are to be accommodated or resolved. And this is an on-going process that

will effect the life of the governance activity.

The above may seem simplistic, but ignoring these issues can

undermine the best intentioned activities. Some examples in Canada include:

-

Significant delays in establishing a Marine Protected Area

(MPA) because a First Nation (aboriginal) group was excluded in the

initial discussions: The MPA program is led by the federal government

which has taken nearly ten years to recognize and understand the

importance of provincial, municipal, and private interests [Leroy, 2002].

-

Ineffectiveness of a provincial policy to limit coastal

development because of lack of trust at the local level despite numerous

“information” meetings: The result was that policy implementation was

delayed for 10 years and inappropriate construction increased in the

meantime to avoid the expected regulations [Nichols, et al., 2006].

-

Lack of comprehensive coastal zone management programs due

to uncertainty and fragmentation in jurisdiction, administration,

ownership, and use of coastal resources: There are not well established

arrangements for collaboration among all of the government agencies at the

several levels involved and each activity causes a new process of

stakeholder identification and consultation. From an information

perspective this has led to a lack of consistent data about interests and

boundaries along the coast.

4. LEGAL ISSUES

Another way of viewing marine governance is through an

analysis of governance functions that link governance to the law and

information. These include the following (Nichols, Monahan and Sutherland,

2000):

-

allocation of resource ownership, control, stewardship and

use within society;

-

regulation of resources and resource use (e.g.,

environmental protection, development and exploitation, rights to economic

and social benefits);

-

monitoring and enforcement of the various interests;

-

adjudication of disputes, including inclusive processes;

-

management of spatial (geographically referenced) and

other types of information to support all of the above functions.

This approach highlights the role of the legal frameworks

within each nation in managing marine space. These frameworks are generally

multi-layered ranging from the United Nations Law of the Sea Convention

(UNCLOS), international customary law, and international treaties to

national, state, and local level laws derived from tradition, legislation,

and the courts.

4.1 The Legal Complexity of Interests in Marine Space

The United Nations Law of the Sea Convention [UN, 1982]

establishes a framework for national and international governance by, among

other provisions, establishing limits of national resource use and control.

However, each nation must also have a set of procedures for allocating

resources within these zones. In many cases, this depends on tradition and

legal frameworks. These frameworks may be defined by the local, regional

(provincial/state) and/or national legal systems and constitutions. Even

when only government interests are considered, the resulting marine/coastal

legal arrangements are usually complex.

To illustrate this complexity, consider the following terms

often used interchangeably or inappropriately [Cockburn and Nichols, 2002]:

-

Sovereignty: supreme rights of ownership; entities

holding sovereign rights reserve the right to impose their will on others

and to usurp the ownership rights of others (e.g. by expropriation). In

international law, to be sovereign means that a state “must be able to

exercise jurisdiction, over a determinate tract of territory,...and have

legally independent powers of government, administration and disposition

over that territory.” [Walker, D, 1980].

-

Legislative Jurisdiction: “[t]he sphere of

authority of a legislative body to enact laws and to conduct all business

incidental to its law-making function.” [Black, 1979] or that aspect of

power where rules (i.e. rights, responsibilities and restrictions) of

social, cultural, economic and political behavior are defined, and wherein

it is determined how and when those rules are applied and enforced.

-

Administrative Authority: “[t]he power of an agency

or its head to carry out the terms of the law creating the agency as well

as to make regulations for the conduct of business before the agency;

distinguishable from legislative authority to make laws.” [Black, 1979].

It is therefore the means by which jurisdictionally defined rules are

applied and enforced.

-

Title or Ownership: the means whereby the owner of

the rights to the object of property has the just possession of that

object (although actual possession or occupation may be by another). Where

sovereign, jurisdictional, and administrative rights are normally rights

vested in governments and their agencies, title may be held by different

levels of government, groups, and individuals. Depending on the legal

system, ‘ownership’ may be full or partial and usually consists of

derivative interests (e.g., lease, use, license, mortgage).

4.2 The Specific Nature of Marine Interests

In theory, land and marine spaces both have this complex

legal regime. However, three characteristics of marine interests make the

complexity more apparent:

-

The legal frameworks are evolving rapidly and therefore

can be incomplete and contain more uncertainty than on land: Although

property and other related law always evolves on land, over the last

century, marine legal frameworks have been changing more rapidly. Causes

include:

-

expansion of national territories under the Law of the

Sea (and consequent boundary and limit delimitation issues);

-

need to clarify intergovernmental title, jurisdiction,

and administration within these expanded territories;

-

rapid development of relatively new marine resource uses

or increasing intensity of existing uses (e.g., petroleum and mineral

exploitation and transportation, coastal development, recreation and

tourism, aquaculture and sea ranching, renewable energy production);

-

emergence of new issues such as conservation and

environmental risk reduction;

-

increasing recognition of the rights of indigenous

groups and other groups in coastal and marine resource.

-

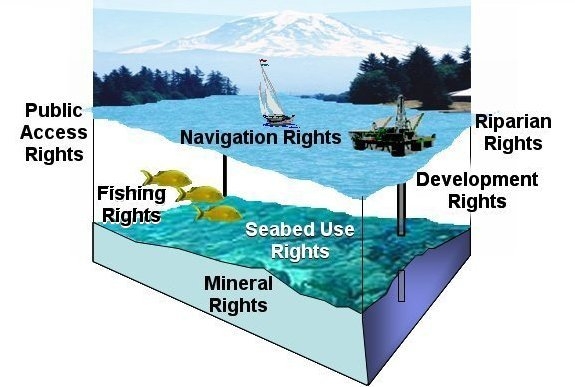

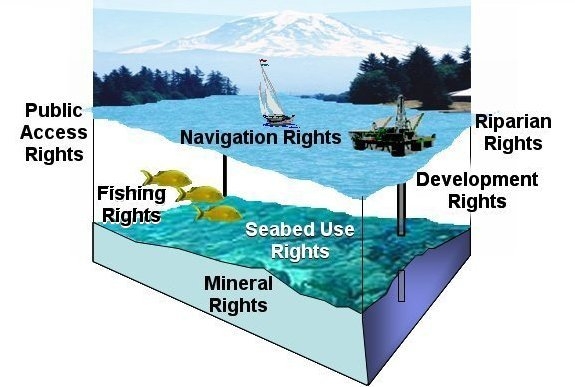

There are virtually no rights of exclusive use or

ownership in marine space: The three dimensional aspect of ‘a parcel’ is

more apparent (Figure 1) than on land because rights are usually allocated

for specific portions (e.g., seabed, water column) or specific activities

(e.g., fishing, navigation). The interests usually coexist and even this

coexistence may change over time (e.g., seasonal rights). This increases

the number of stakeholders that must be considered for any marine/coastal

area. It also results in myriad boundaries of jurisdiction,

administration, ownership and use – in some instances, a boundary or limit

for each specific resource or activity.

Figure 1: 3-Dimensional Marine Parcel

(From Sutherland [2005])

-

Interests in marine space tend to come in smaller

‘packages’: Related to the first point is the fact that the management of

marine interests tends to focus on specific resources or activities rather

than geographic areas. On land, for example, we package spaces as:

-

state land vs. private land;

-

federal land vs municipal land;

-

exclusive rights of surface ownership such as freehold,

which include fixtures (e.g., trees, buildings, and at least some

subsurface rights).

This fragmentation of interests is also usually reflected in

(or caused by) the institutional structures of government. Thus the Ministry

of Fisheries may administer an area of marine space for fishing and related

activities and the same space is subject to different regulations for

navigation that is regulated by the Ministry of Defense. One result is the

fact that information about the stakeholders, their interests, and

activities is widely scattered throughout government.

4.3 The Elusive Land-Water Interface

Much of marine activity is focused on the coast. Similarly,

the intensity of land use in many countries is greatest at the coast in

large part because of traditional transportation and shipping through ports.

The result is that the number of stakeholders, the opportunities for

conflict among their interests, and the value they or society places on

those interests is at a maximum at the coastline. This results in and is

affected by the following issues, among many others:

-

Overlaps and gaps: There are often overlaps of

jurisdiction, administration, and ownership between government bodies that

are primarily land based and those that are marine based (e.g., in ports

where land and marine activities are intertwined). One consequence is that

information about those interests may not only be fragmented but also

inconsistent and incomplete;

-

Complex private and public interests: Private land

interests frequently extend into marine space (e.g., rights for wharf

development, littoral rights associated with upland ownership, traditional

rights to areas for fishing through weirs). In many cases these rights are

undocumented and have been acquired through traditional use. Furthermore,

these rights are not usually well understood by planners, managers, and

policy makers without a water law background. An additional complexity is

that there are emerging or increasing interests such as the public right

to access beaches and to have environmental protection of endangered

habitats. Such public interests typically clash with private interests,

and in many cases neither are well defined or documented.

-

Lack of appropriate information for traditional governance

practices: Information about coastal interests is generally not well

managed because, for example:

-

there are numerous government agencies involved

resulting in fragmented, duplicated, incomplete and inconsistent

datasets;

-

historical datasets are often incomplete and out of date

because there was little concern until recently;

-

no one agency (and in some cases no specific level of

government) has the responsibility to lead data management activities in

both coastal land and marine spaces.

-

Boundaries and limits are not well delimited: Boundaries

and limits in the coastal zone are typically made with reference to

physical features, many of which are difficult to clearly define or

relocate (e.g., high water, the shoreline, the normal baseline). The land

water interface is ambulatory and traditionally most boundaries and limits

followed the motions of that interface. Today greater emphasis is placed

on ‘fixing’ these lines. This may be driven by law (e.g., nations

generally declare their national baselines under the Law of the Sea at a

point in time for offshore boundary delimitation); by institutional

structure and practice (e.g., the municipal coastal boundaries defined on

a map); or by technology (e.g., the desire to establish co-ordinates or

boundaries for geographical information systems). However, for the most

part, the law only delimits boundaries when, and if, an issue arises.

Therefore without court decisions or specific legislation the location of

many boundaries is a matter of considerable interpretation [Sutherland,

2005].

5. TECHNICAL ISSUES

5.1 The importance of information

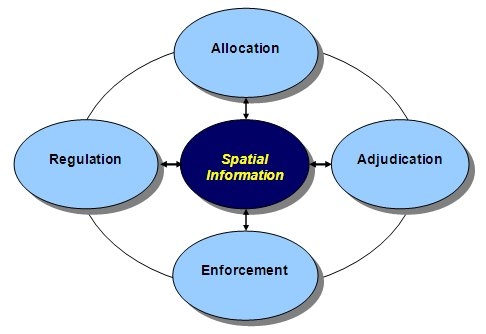

Information is an essential technical component of the

governance of marine spaces. Information on resources that currently exist,

the nature of the environment within which those resources exist, as well as

on the users and uses of those resources is always a requirement for

effective evaluation and monitoring of marine areas. Information on, for

example, living and non-living resources, bathymetry, spatial extents

(boundaries), shoreline changes, marine contaminants, seabed

characteristics, water quality, and property rights can all contribute to

the sustainable development and good governance of coastal and marine

resources. All of these types of information have spatial components and

therefore spatial information is important to the good governance of marine

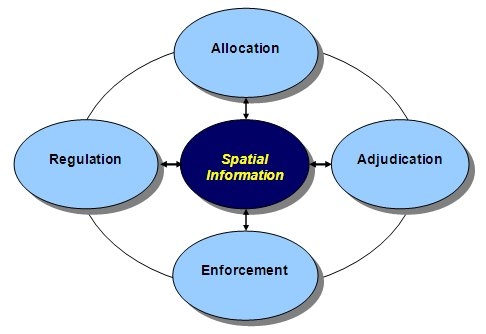

spaces (Figure 2) [Sutherland, Wilkins and Nichols, 2002].

Figure 2: The role of spatial

information in governance

(From Nichols, Monahan and Sutherland, 2000)

Boundary information is one type of spatial information that

is essential in the management and administration of marine spaces. However

in some cases it may be better not to focus on boundaries, as boundary

uncertainties (e.g., as with federal and provincial boundary uncertainties

in some coastal regions in Canada) are sometimes the cause of social and

administrative conflicts in coastal and marine spaces. Recent governance

research supports the relevance of imprecise or ill-defined boundaries

insofar as the existence of these boundaries is not a catalyst for dispute

[Nichols, Monahan and Sutherland, 2000]. The precise delimitation of

boundaries usually become important in relation to the need to allocate

equitable resources perceived to be dissected by the potential boundary

[Hildreth and Johnson, 1983]. For example, such is the case with the

boundary dispute between Nova Scotia and Newfoundland [Arbitration Tribunal,

Nova Scotia-Newfoundland Dispute, 2002].

5.2 The issue of four-dimensional rights in marine spaces

When considering marine environments from a right-based

perspectives, one ought to consider that in one column of the marine

environment there are rights to the surface of the water column (e.g.

navigation), to the water column it self (e.g. fishing), to the seabed (e.g.

fishing and mineral resources), and to the subsoil (e.g. mineral resources).

The very nature of the marine environment requires that rights be considered

in terms of at least three dimensions, in snapshot, and more practically in

four dimensions considering that rights to marine spaces change over time.

Technically, therefore, tools developed to manage and administer rights to

marine spaces should consider the inherent multidimensional nature of those

rights [Ng’ang’a et al, 2004].

5.3 Dealing with multiple interests for the same space at

the same time

Concepts such as the marine cadastre or marine

administration systems have been discussed in many academic papers as

technical means for aiding in the management and administration of rights in

marine spaces. Any technical tool such as a marine cadastre or marine

administration system is faced with the challenges of not only dealing with

the multidimensionality of rights to marine spaces but also with the fact

that in many international jurisdictions there is the added complexity of

overlapping interests (e.g., jurisdictional rights, administrative rights,

title, leases, customary rights, aboriginal rights, public rights, etc.).

The design of marine information systems dealing with the management of

rights information ought to take the possibility of overlapping and

co-existing rights into consideration [Ng’ang’a et al, 2004].

5.4 Fitting into larger ‘information’ initiatives

The management of marine spatial information is an asset to

the efficient management of marine resources, and can in many instances help

to avoid minimize conflict among the many stakeholders. Recognizing this,

and the fact that no one stakeholder possesses all necessary information,

many jurisdictions have begun initiatives to better manage coastal and

marine spatial information and to apply information technology and concepts

to the management of marine spatial information [Ng’ang’a et al, 2004;

Nichols, Monahan and Sutherland, 2000].

In order to coordinate the dissemination of marine spatial

data that can support good governance of coastal and marine spaces, marine

geospatial data infrastructure initiatives are underway in many parts of the

world. Initiatives such as Canada’s Marine Geospatial Data Infrastructure

(MGDI) and the U.S. Federal Geographic Data Committee (FGDC) are considering

the information and other infrastructure components necessary to provide

geographically dispersed stakeholders with spatial data to support

governance decision-making. Regional bodies such as the Permanent Committee

on GIS Infrastructure for Asia and the Pacific (PCGIAP) are also taking

steps to implement marine geospatial infrastructures.

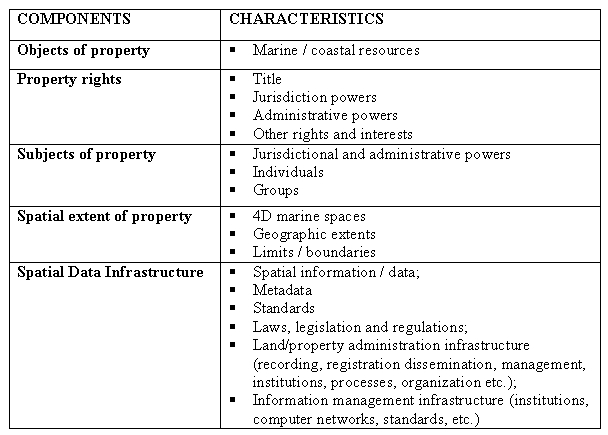

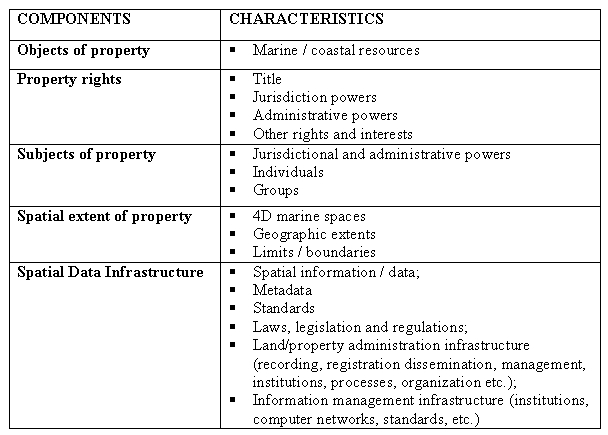

The components of any marine geospatial data infrastructure

are expected to include key spatial data, computer network infrastructures,

spatial data management software and other software, data- and other

standards, metadata, stakeholders, and possibly a spatial data

clearinghouse. Table 1 shows spatial data infrastructures as part of a

marine information system from a property rights perspective.

Table 1: Components of a Marine

Information System from a Property Rights Perspective

(After Sutherland, 2005)

5.5 Issues in defining coastline boundaries

Tidal boundaries along coasts in North America are defined

in law either by the “intersection of a specific tidal datum with the shore”

or by “tide marks left on the shore by the receding waters of a particular

stage of tide” [Nichols, 1983]. Internationally this is more or less true.

Because tidal datums are related to specific sea levels and therefore

subject to temporal and spatial variations, and because the marks left by

tidal actions on shores also vary with the changes in sea level and tides,

boundaries defined by these methods are sometimes subject to ambiguous

positioning in 3-dimensional space.

Constant tidal action against the shore can cause the

deposit of material on the shore or the erosion of shore material and

therefore the physical configurations of shorelines are subject to constant

change [Flushman, 2002; Lamden and de Rijcke, 1985; Nichols, 1983]. This

means that resurveys are sometimes necessary in order to keep coastal

boundary information up to date. These and other factors are issues in

defining coastline boundaries and therefore indirectly affect the governance

of marine spaces since, for example, the implementation of jurisdictional

and administrative rules and regulations often depend upon defined

boundaries.

5.6 Science and Local Knowledge

As on land, traditional or local knowledge can play an

important role in marine governance. Unfortunately the value of local

knowledge is not always appreciated or is ignored because: it is not

standardized; it is not considered ‘objective’; or it is difficult to

obtain. However science has only begun to give a picture of the vast ocean

territory, even near the coast. We have snapshots and sporadic data, which

like lead line depth measurements, leave much to be discovered and

understood. Local knowledge is an asset not to be underestimated in filling

in those gaps, validating the scientific sample and theories, or in

understanding the interconnection within ecosystems. Fishers along the East

and West Atlantic coasts, for example, could have advised the scientists who

helped governments who established fishing quotas in the 1970s-1990s that

many north Atlantic the fish stocks were declining, long before the science

driven government policies endangered the fishing resources.

6. DISCUSSION

Marine cadastres and other marine administration information

systems have been proposed as technical solutions to the management of

information about interests in marine resources in support of coastal and

ocean governance. It is easier to design such systems to be useful for

managing information on single activities or resource use (e.g., petroleum

leases) occurring in marine spaces. However, in order to be of maximum

benefit to the governance of marine spaces these information systems will

have to be able to manage and visualize information on multiple marine

resource interests that overlap in 3-dimensional space, and time. These

systems should also function in an environment of efficient and effective

governance and legal frameworks, and optimal institutional arrangements that

meet the often diverse needs of identified and engaged stakeholders.

Therefore, we would like to propose that activities affecting the rights and

responsibilities, including information management, need to consider the

following:

-

A multidisciplinary approach is needed in the governance

of marine spaces. Surveyors, lawyers, planners, and resource managers all

understand part of the picture. To be complete or even useful, any

information system to support marine governance needs to reflect the

variety of interests, their complexity, and the unique aspects of marine

interests.

-

The emphasis should not necessarily on precise boundary

delimitation. Many of the boundaries and limits are undefined or

un-delimited until an issue arises. Others are fuzzy or moveable by nature

and best serve the interest of stakeholders that way.

-

The sheer number of overlapping and coexisting interests

in four dimensional space means that new approaches to presenting

appropriate information are needed. Rather than imposing a land-based

system (i.e., grids, straight lines and co-ordinates), the focus should be

on helping stakeholders and decision makers visualize the complexity and

multiplicity of interests.

-

Co-management arrangements may be a better option than

management of zones and geographical areas defined by boundaries if

governance is to be inclusive and recognize all interests. Co-management

(e.g., networking of information sources) will also be necessary in

developing truly useful information systems, rather than a single agency

approach.

The oceans provide an opportunity to not make the same

mistakes we have made in land resource management and land information

systems. Perhaps what we can create for marine space can help to improve our

governance and information systems on land.

REFERENCES

Arbitration Tribunal, Nova Scotia-Newfoundland Dispute

(2002)

http://www.boundary-dispute.ca/. Accessed March 2002.

Black, H. C. (1979). Black’s Law Dictionary Fifth Edition,

by Henry Campbell Black (5th Ed. By the Publisher’s Editorial Staff), West

Publishing Co., St. Paul, Minn. 1979.

Charette, N. and A. Graham (1999). "Building partnerships:

Lesson learned." In Optimum, Vol. 29, No. 2/3.

Chiarelli, B., M. Dammeyer and A. Munter (1999). "Why

regions matter: Perspectives from Europe and North America". In Gouvernance,

No. 1, March.

Cockburn, S. and S. Nichols (2002). “Effects of the Law on

the Marine Cadastre: Title, Administration, Jurisdiction, and Canada’s Outer

Limit.” Proceedings of the FIG Congress, Washington DC, USA, April 24, 2002.

DeBlois, P. and G. Paquet (1998). "APEX Conference 1998:

reflections on the challenges of governance." In Optimum, Vol. 28, No. 3,

pp. 59-69.

Flushman, B. S. (2002). Water Boundaries: Demystifying Land

Boundaries Adjacent to tidal or Navigable Waters. Wiley Series in Surveying

and Boundary Control.

Handy, C. (1996). "Finding sense in uncertainty." In

Rethinking the Future: Rethinking business, principles, competition, control

& complexity, leadership, markets and the world. Reprinted (1997). Ed.

Gibson, R., Nicholas Brealey Publishing, London.

Hildreth, R. and R. Johnson (1983). Ocean and Coastal Law.

Prentice-Hall, Inc., New Jersey.

Hoogsteden, C., B. Robertson, G. Benwell (1999). "Enabling

sound marine governance: Regulating resource rights and responsibilities in

offshore New Zealand." In Proceedings of the New Zealand Institute of

surveyors & FIG Commission VII conference & Annual General Assembly, October

9-15.

Kyriakou, D. and G. Di Pietro (2000). "Editorial." In The

IPTS Report, No.46, June 2000.

Lamden, D. W. and I. de Rijcke. (1989). “Boundaries.” In

Survey Law in Canada: A collection of essays on the laws governing survey of

land in Canada. The Canadian Institute of Surveying and Mapping; Canadian

Council of Land Surveyors; Carswell Toronto • Calgary • Vancouver

Leroy, A.S. (2002). "Public Participation and the Creation

of a Marine Protected Area at Race Rocks, British Columbia". Masters of

Science in Planning Thesis, School of Community and Regional Planning,

University of British Columbia, 137pp.

Manning, E. (1998). "Renovating governance: lessons from

sustainable development." In Optimum, Vol. 28, No. 3, pp. 27-35.

Masson, C. and S. Farlinger (2000). " First nations

involvement in oceans governance in British Columbia." Paper presented at

Coastal Zone 2000 conference, Saint John, NB, September.

Meltzer, E. (2000). "Oceans governance: A paradigm shift or

pipe dream?" Paper presented at Coastal Zone 2000 conference, Saint John,

NB, September.

Ng'ang'a, S. M., M. Sutherland, S. Cockburn and S. Nichols

(2004). "Toward a 3D marine cadastre in support of good ocean governance: A

review of the technical framework requirements." In Computer, Environment

and Urban Systems, 28 (2004), pp. 443-470.

Nichols, S. (1983). “Tidal Boundary Delimitation.” Technical

Report # 103, Department of Geodesy and Geomatics Engineering, University of

New Brunswick, Canada.

Nichols, S., D. Monahan and M. D. Sutherland (2000). "Good

Governance of Canada’s Offshore and Coastal Zone: Towards and understanding

of the Maritime Boundary Issues." In Geomatica, Vol. 54, No. 4, pp. 415-424.

Nichols, S., O. Chouinard, H. Onsrud, M. Sutherland, and G.

Martin [2006]. “Adaptation Strategies” Section 4.8 in Impacts of Sea-Level

Rise and Climate Change on the Coastal Zone of Southeastern New Brunswick,

R. Daigle, ed., Environment Canada (in press).

Paquet, G. (1994). "Reinventing Governance." In Opinion

Canada, Vol. 2, No. 2, April.

Paquet, G. (1997). "Alternative service delivery:

Transforming the practices of governance." In Alternative Service Delivery:

Sharing governance in Canada. Eds. Ford, R. and D. Zussman, KPMG • The

Institute of Public Administration • University of Ottawa Libraries.

Paquet, G. (1999). Governance Through Social Learning.

University of Ottawa Press.

Paquet, G. (2000). "Subsidiarity is an ugly but powerful

design principle." In The Hill Times, Ottawa, October 2nd

Rosell, S. A. (1999). Renewing Governance: Governing by

learning in the information age. Oxford University Press.

Savoie, D. J. (1999). Governing from the Centre: The

concentration of power in Canadian politics. University of Toronto Press.

Sutherland, M. D. (2005). “Marine Boundaries and the

Governance of Marine Spaces”. Ph.D. Dissertation (University of New

Brunswick) and University of New Brunswick technical paper, 2005.

Sutherland, M. D., K. Wilkins and S. Nichols (2002).

"Web-Geographic Information Systems and Coastal and Marine Governance." In

Optimum, Issue 3, Spring 2.

United Nations (1982). United Nations Law of the Sea

Convention. New York: UN.

Walker, D.M. (1980). The Oxford Companion to Law. Oxford:

Clarendon Press.

BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES

Dr. Michael Sutherland is a graduate in land

information management from the Department of Geodesy and Geomatics

Engineering, University of New Brunswick, Canada. He is currently engaged in

marine environment-related research activities at the School of Management,

University of Ottawa and Department of Oceanography, Dalhousie University,

Canada. He lectures part-time at Ryerson University, Canada. Michael is a

member of the Canadian Institute of Geomatics, and is Chair of the

International Federation of Surveyor’s Working Group 4.3, Commission 4

(hydrography, coastal zone management, ocean governance, and marine

cadastre).

Dr. Sue Nichols is a Professor in Land Administration

and Property Studies at the University of New Brunswick and has conducted

research on tidal and marine boundaries for over 20 years. Sue is a

Past-President of the Canadian Institute of Geomatics and has been on the

Advisory Committee for the Canadian Minister of Natural Resources. She

engaged in research as Project Leader on a multi-year, interdisciplinary

research project on "Good Governance of Canada's Oceans: The Use and Value

of Marine Boundary Information" that included examination of boundary

uncertainty, marine cadastre, and other issues related to ocean governance.

CONTACTS

Michael Sutherland, Ph.D.

School of Management

Vanier Hall, Box 141

University of Ottawa

136 Jean-Jacques Lussier Privée

Ottawa, Ontario, K1N 6N5

Tel. + 1 613 562-5800 ext. 4920

Email:

michael.d.sutherland@unb.ca

Sue Nichols

Professor and Director of Graduate Studies

Dept. of Geodesy and Geomatics Engineering (GGE)

University of New Brunswick

Fredericton, NB

Canada E3B 5A3

Tel: + 1 506-453-5141

Fax: + 1 506-453-4943

E-mail: nichols@unb.ca

|